NARRATIVE IN PHOTOGRAPHY AND ITS MEANING

NARRATIVE IN PHOTOGRAPHY AND ITS MEANING

Two years from the start and after the postponements due to the coronavirus situation, I finally got myself fully immersed in the preparation of the project on JMW Turner. I was thinking how to actually introduce the upcoming four blog posts about this brilliant painter that I am about to offer to you. When, after some time, I returned to my own texts I found out that my own opinions have shifted over the past two years. In the end, I decided to write a short reflection about the meaning of narrative behind a picture.

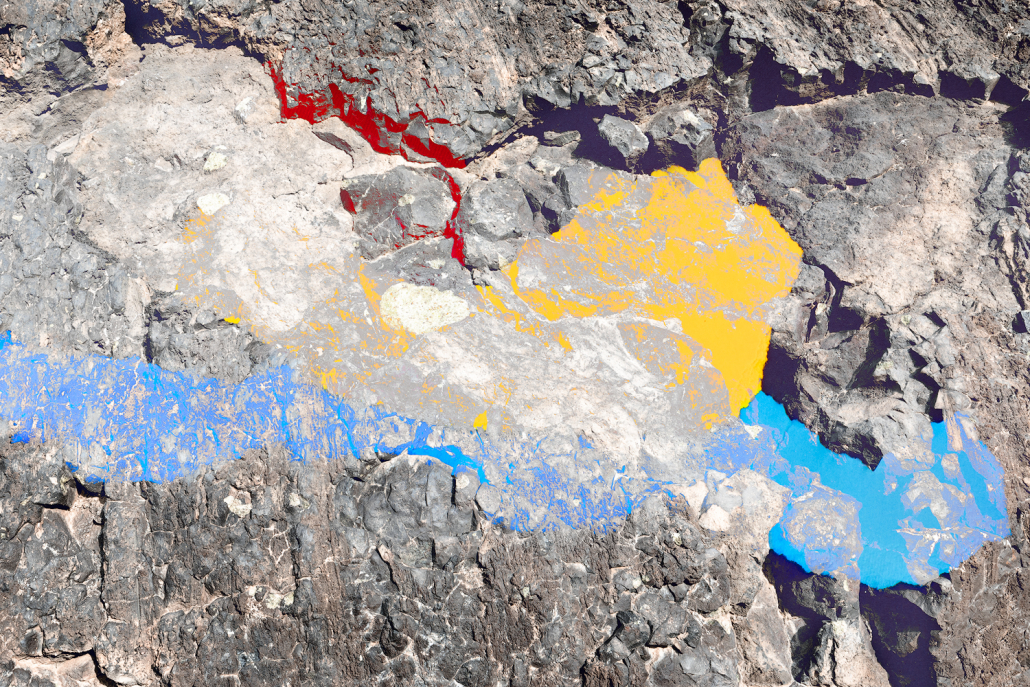

Manrique #T-04

Since 2015 I have been systematically working on projects – first focused on writers and now on prominent painters. I always choose art protagonists who distinctly differ from one another and, at the same time, allow for my own development. No matter how logical it may seem that stories are a clear part and maybe even the outset of the works I made in the cycles about Mácha, Andersen and Exupéry, it may not be so clear with regard to projects dedicated to painters which I started two years ago with César Manrique.

Nevertheless, it is much clearer in the case of Turner. When reading all kinds of monographs dedicated to this painter, I came across multiple essays on the ways in which Turner stood apart from other landscape artists of his time. It may seem that he owed his success to his excellent technique, the manner of capturing and processing light for his time so advanced, or simply because of his incredible diligence and good luck with clients or the positive reception of his work by both the general public and professionals.

Yet that would be the full truth and I dare say I am convinced that it would be a misleading shortcut to say so. JMW Turner put great effort into approaching his landscapes complexly, that is, he would often reflect on contemporary development in England and Europe. Turner lived through a time of key social and political changes – the whole Napoleonic era starting with Napoleon entering the political scene and his infamous end in St Helena, he lived through the wars with France and Spain, during his time, the Declaration of Independence was pronounced in America, steam powered railway passenger transportation started and the first steam ship crossed the Atlantic. And Turner was able to respond to all these in his work – through choice of subjects, colours, symbolism. Besides that, he was the genius who significantly developed and shifted the use of watercolours including continuous testing of new materials – both paints and paper.

What can Turner’s example bring to my work – or to that of anybody else who has greater artistic ambitions than sharing a successful landscape photograph?

Surely, like me, you have been drawn into a debate about which photograph or painting is better, more accomplished, more important. These debates seem endless and are most likely to remain so. I myself have heard so many possible explanations… Starting with the claim that it is the author’s name that sells a painting or photograph and that the success of a painting or photograph is measured by the price for which it was sold at an auction, or whether the author is just lucky or is skilfully navigating somewhere in the middle of the mainstream. No matter what the truth is, it can be seen in Turner’s case that the more successful paintings and photographs tell a story – they are more than postcards. Just look for yourselves in art galleries or at the photographs that rightfully win international competitions. In most cases they depict or represent an event, either historical or contemporary, or an inner story, hidden to the eyes of the observer to provoke thinking. Quite often the manner in which they were produced also speaks about the skills or experience of their creator. In other words, technical skill, creativity, inspiration, and the addressed subject walk hand in hand.

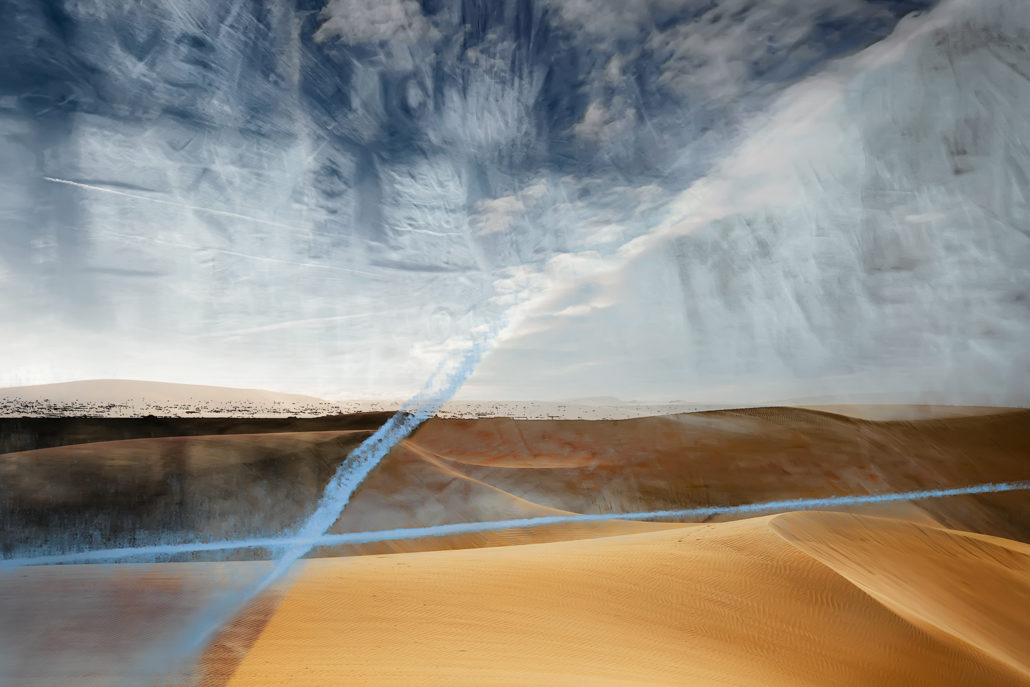

But how to cope with all of this in photography? In my projects, I tried a variety of methods. From purely emotional photography influenced by the beauty of Lake Mácha to intense research and the creation of scripts for the individual photographs or artwork in the case of Exupéry. After all, with writers it is quite simple because they provide you with a script in their books. With painters it is trickier because, in their case, the final visual artwork already stands out on its own and you can get inspired by it but should not get overridden. And so, you need to answer the logical questions:

- Which subjects did the painter address?

- Were they contemporary or historical subjects?

- Why did he use that particular colour palette?

- Which medium did he use for painting and why?

- Do the paintings he created form a part of a certain life period or reflect some realization he made?

- How can all of this help me, coming some 50, 100, or in Turner’s case, 200 years later?

- Can I make his stories relevant to our current situation and how?

- How do I cope using my photographic means in relation to painting?

- How do I prevent being accused of stealing?

SaintEx-07

Regular photographers standing in the countryside trying to capture the scenery before them rarely pose such questions to themselves. And that is what, in my view, sets extraordinary photographs/paintings aside from the others – the effort to tell a story, to position it within our reality – and if fortune has it, then also the ability to convey the chosen subject in a form attractive to the audience.

Nevertheless, you could say that all of this will not necessarily bring you success. In Turner’s case, it is interesting to observe two lines – the artistic line represented by oils and large canvases usually painted for exhibitions at the Royal Academy or on commission for rich clients, and a commercial line represented mostly by watercolours, which Turner frequently used to sustain himself and also to keep as notes from his journeys. While he often had to face criticism with his oils and was not always able to sell his paintings, his watercolours were selling like hot cakes – both as individual artworks and as templates for etchings. To what extent can anyone perceive and admit to oneself openly which subjects and forms are those that can sustain them and which represent their “big art”? This dilemma is shared across all human activities. There are activities and products which are fundamental, great, important for further development, but perhaps difficult to sell, and then there are products, services and activities that might not sell at such a high price but which can be sold regularly and which generate a relatively stable interest.

Without wanting to imply anything or further comment on it, it is important for me to keep a line of narrative in my work. I probably would not be able to go to the Lake District (Note: Project on Turner) or to Lanzarote (note: projects on Exupéry and Manrique) and just take pictures of the landscape. That was done by many before me and often much better than I am capable of. But that is not important, that is not the reason why I do photography and my projects. Of course, I do try to reach maximum technical skill both in taking photos, editing or the final presentation, however, what is much more important for me is whether I am able to process, interpret and present the stories I have chosen and believed that I wanted to show to the public and that it matters – even if just for me.

Liberec, 20.3.2022

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!