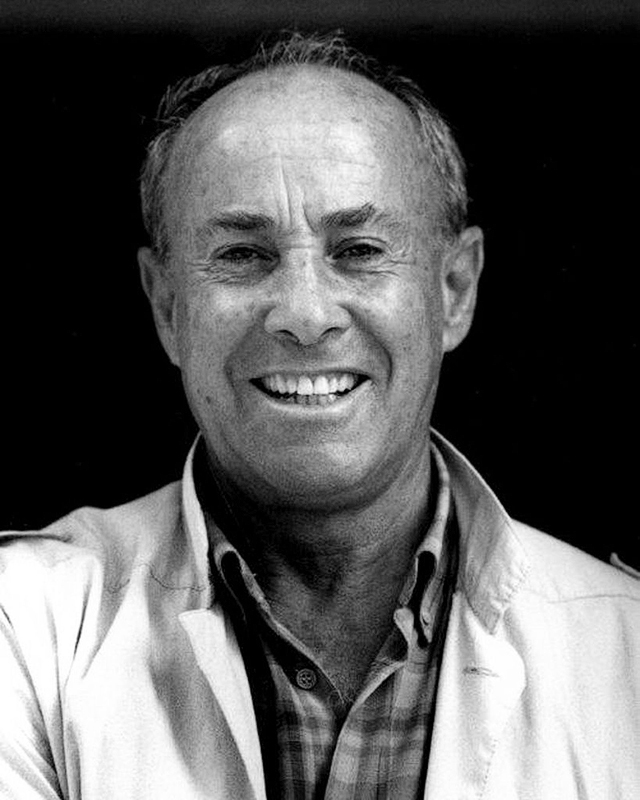

César Manrique: 1919 (Arecife) – 1992 (Haria/Tahiche)

Personally, I find César Manrique to be such an interesting personality that I have decided to dedicate a separate blog post to him. During our photo expedition we visited places where he lived and worked, we saw his paintings and architectural works “in natura”, along roads and next to crossroads we would pass by his “pinwheels”, we passed through the crossroad where, on his way to the Foundation, at the age of 73, he died in an accident when he did not give way to another car…

Personally, I find César Manrique to be such an interesting personality that I have decided to dedicate a separate blog post to him. During our photo expedition we visited places where he lived and worked, we saw his paintings and architectural works “in natura”, along roads and next to crossroads we would pass by his “pinwheels”, we passed through the crossroad where, on his way to the Foundation, at the age of 73, he died in an accident when he did not give way to another car…

Manrique was a crucial personality for the development of Lanzarote in the past half century. Thanks to him the island serves as an example of sustainable care for its natural wealth, architecture and urbanism – height regulation of tall buildings, limits on billboards, regulation of recreational facilities and so on… On visiting his house and the Foundation one can clearly perceive his respect for the natural materials of the island and thereby his opinion of what is important in the life of man and what is not. For the following text I used the book “CÉSAR MANRIQUE – PINTURA” to support my statements.

Contexts of Work

The life of César Manrique is framed by the civil war and the start of General Franco’s rule (up to 1975) on the one end and the World Expo in Sevilla and the Barcelona Olympic Games that were celebrated as the climax of internationalization of Spain’s cultural and social reality. Undoubtedly, he was influenced by “three worlds” – the Canary Islands where he was born and where he lived, his allegiance to Spain, which he was proud of, and experience from living abroad (Paris, New York) where he asserted himself as an artist.

He was born in Arecife in Lanzarote. Since childhood he had artistic tendencies and often wondered whether he was an “oddball” because he wanted and did things that his friends had absolutely no interest in (or were frankly bored by them): he would search for stones with unusual shapes, admire the colours of a flower, he would observe the zigzag flight of a butterfly or the spasmodic leaps of insects … and he would often capture them in his initially naïve drawings (where have I read this before… perhaps Leonardo?).

Madrid

César Manrique came to Madrid in 1945 during the rule of General Franco. He started his studies at the San Fernando art school despite being 26 years old already and having held several solo exhibitions in Arecife and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. He was eager to get first-hand knowledge to stabilize his precarious insular experience and he wanted to learn painting techniques and methods that would allow him to better express what he had done until then.

“The mechanics of painting is […] of primary importance for me. Without a command of craftsmanship no one can do anything worthwhile”.

In Madrid of the late 1950s the main artistic trend was the abstract “Art Informel”.

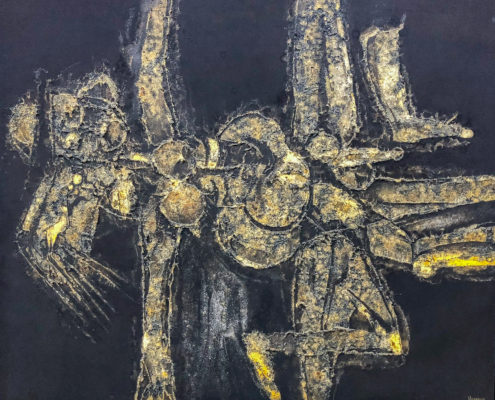

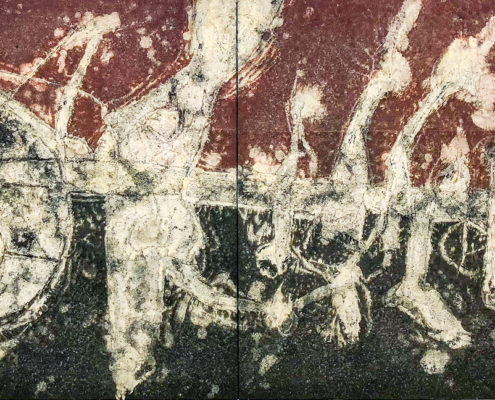

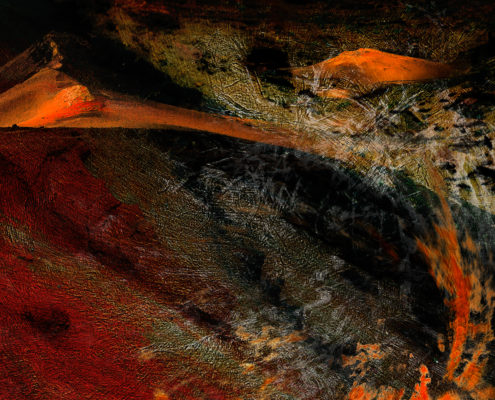

The painters of the Art Informel style were particular about the disorganized, intuitive chaos in their artwork. They would usually express feelings of horror, solitude, anger, or existential anxiety. They used thick layers of paint combined with pieces of stucco, ground marble, sand or even plaster. Manrique, while initially strongly influenced by Picasso’s cubism or Matisse’s colour palette, gradually inclined towards the expression of Informel. He departed from the colourfulness and geometric lines and around 1958-9 he introduced the morphology of the island of Lanzarote into his works.

He focused on researching work using local materials. Linear patterns vanished and were replaced by materials with strong and evident relief, which he turned into the most distinctive element of his paintings.

“My style is in the artistic line of a virgin world, a world undergoing formation (…). The forms that, I bring to my canvas are the forms of a world with no dawn, on the first day. They’re nature uncatalogued, without academic notes (…) nature is just beginning (…).”

At the end of the 50s, Manrique was already internationally clearly recognizable. As stated by critics: ….. “César Manrique’s palette, previously so vital and polychromatic, is restricted to the solemnity of black and white, their grey offspring, tanned ochre and the mother earth”

From Madrid to New York and back to Lanzarote

While Spain of the late 1960s continued developing Informel and its alternatives, César Manrique moved his studio to New York. In the post-war years Art Informel became a sort of “lingua franca” enabling artists’ communication beyond national borders. Gradually it also became a form of protest instigating against the possible consequences of war that would use nuclear weapons including the devastating effect on mankind and the whole planet. However, when Manrique came to New York, in contrast to Spain, abstract expressionism no longer prevailed. The dramatic death of Jackson Pollock in 1956 brought expressionist adventures to a symbolic end.

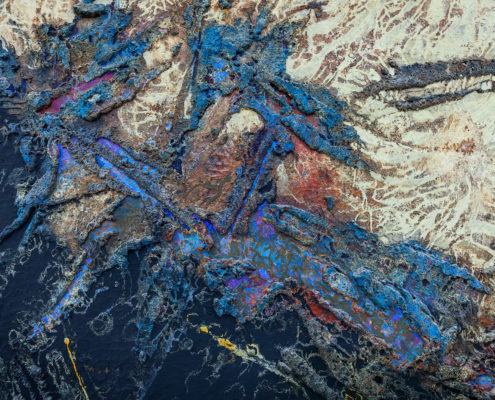

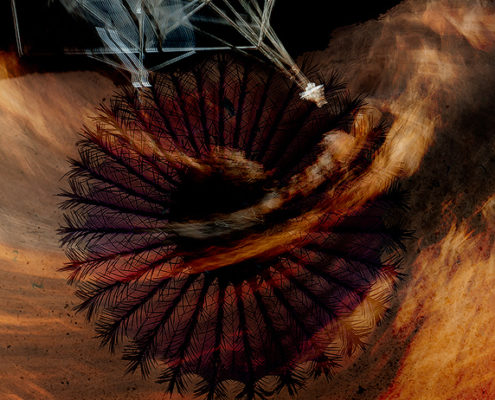

For this reason, in 1968, after having spent four years in New York, Manrique decided to definitely return to Lanzarote – it is possible that his encounter with land-art, a series of artistic designs the aim of which was to introduce new harmony between art and nature, played a role in making the decision. His new paintings done in New York were characteristic with the use of casein, paste and varnish reinforced with acrylic paint. They differed from the previous works not in content, but in a totally renewed concept of colour and space. New York unquestionably had a considerable impact on Manrique and was very likely the source of his new colour scale. In the 1965 canvases, colour has a very vivid tone and emits nearly metallic light, like the colours in caves when the beam of a flashlight bounces off the quartz, basalt and mica.

For this reason, in 1968, after having spent four years in New York, Manrique decided to definitely return to Lanzarote – it is possible that his encounter with land-art, a series of artistic designs the aim of which was to introduce new harmony between art and nature, played a role in making the decision. His new paintings done in New York were characteristic with the use of casein, paste and varnish reinforced with acrylic paint. They differed from the previous works not in content, but in a totally renewed concept of colour and space. New York unquestionably had a considerable impact on Manrique and was very likely the source of his new colour scale. In the 1965 canvases, colour has a very vivid tone and emits nearly metallic light, like the colours in caves when the beam of a flashlight bounces off the quartz, basalt and mica.

„Lanzarote is MY TRUTH“

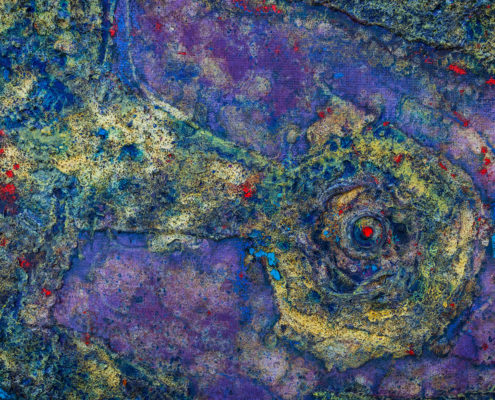

On returning to his home island, the themes of his paintings changed significantly. If earlier, it was the crops of his island, Lanzarote, and the wise and millenary ways of using a nearly barren soil, that inspired his paintings, then, in possession of an elaborate technique, nude mountains and cones of volcanoes started presiding over his work.

On returning to his home island, the themes of his paintings changed significantly. If earlier, it was the crops of his island, Lanzarote, and the wise and millenary ways of using a nearly barren soil, that inspired his paintings, then, in possession of an elaborate technique, nude mountains and cones of volcanoes started presiding over his work.

“All my painting is, essentially, volcanology and geology.”

„Immersed in the calcinated magmas of Timanfaya, direct contact with the volcano kindles an urge for absolute freedom and a strange premonitory feeling, a clear insight into space and time“.

Confronted with the ambivalence of fire, which is both destructive and formative, César Manrique proposes a magical neutralisation of these forces in his pictorial work. As in volcanic eruptions, the artist controls the transition of liquid to solid. The lava solidifies due to the cooling of the incandescent mass, which forfeits its liquidity to become a solid and stable body, subject only to the laws of material erosion or wear. His naturalism is clearly symbolistic and therefore precludes any impressionistic interpretation.

„I have always sought in nature its essential condition, its hidden sense: the meaning of my life. The wonder and mystery which I have found on that long exploratory trail are as real, as apparent, as tangible reality.“

Painting was the core that nourished all his creative activity. He regarded painting to be a sort of research, a fact that confirms the idea that all his findings in other fields (architecture, design, sculpture) were no more than the development of forms that he had “experimented” with on canvas.

Is it at all possible to approximate Manrique’s work in photography?

Honestly, that was the main challenge and goal of our photo expedition. After all, the outcome of photography does not employ substance in 3D and can only make use of contrast, shadow, and colours in the final print… or multiple exposure and ICM, to mention my favourite tools. Does it even make sense to attempt to replicate the visual aspect of his paintings or should one rather concentrate on Manrique’s principles and his creative process, the subject matter of his paintings? His fascination with nature before the “first day” and shapes before they get “academic notes”? How can these elements be combined? Will it help if I take a picture of Manrique’s painting, i.e. transfer it to 2D and then analyze the resulting effect?

We climbed quite a few hills, took photos of material structures in caves, on volcanic slopes, on the seacoast and searched for a rhythm in matter, a “transition of state”. To judge how we managed to cope with the challenge will be up to you when we gradually present them. What was most important though, was process of discovery during our fieldwork. And because we each have our own photographic style; I cannot wait to see the results of my expedition friends’ work – some examples of my work are attached in the gallery of this post.

In Liberec, 16.5.2019